The brightly coloured arcade machines that once flickered in shopping centres and seaside halls were once an integral part of pop culture. Arcade video games followed a full trajectory of rise, flourishing, and collapse, from the first simple screens to complex fighting simulations. According to Professor Andrej Spiridonov of Vilnius University’s Faculty of Chemistry and Geosciences, their history resembles biological evolution: “Arcade games emerged, thrived, declined, and today some still exist as a kind of living fossil.”

Together with Prof. Spiridonov, the evolutionary history of arcade games was reinterpreted by an international, interdisciplinary research team – lead by Prof. Sergi Valverde (Institute of Evolutionary Biology, Barcelona, Spain), Dr Blai Vidiella (CNRS Station for Theoretical and Experimental Biology, France), and Prof. R. Alexander Bentley (University of Tennessee, USA). The group drew on the archiving database MAME, which contains thousands of historical arcade games. This unique collection allowed researchers to observe how genres, hardware, and collaboration networks evolved across four decades. The study was published in the journal “Evolutionary Human Sciences”.

Timeless icons and forgotten hits

Arcade machines rose to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s, with early titles such as Pong (1972) and Space Invaders (1978) appearing in shopping centres and amusement halls. They became not only a technological novelty but also a social phenomenon: places where young people gathered, competed, and shared new experiences. The “arcade boom” of the late 1970s soon spread worldwide. Yet by the late 1980s and early 1990s, as personal computers and home consoles spread, arcade popularity began to decline sharply.

“Arcade machines were not only hardware novelties. They became meeting points, social hubs where a new urban culture was emerging,” Prof. Spiridonov notes.

As in biological evolution, in cultural evolution, what matters is not only quality but also the order of appearance. The first games to reach a level higher than the background had a much greater chance of long-term viability than later compositions based on them, even if the latter were in some respects superior.

“Not all arcade games shared the same fate. Classics like Pac-Man or Street Fighter II today serve as signs of a universal visual language, easily recognised even by those who never played them. Early maze games, by contrast, could not offer the same lasting symbolic value,” Spiridonov explains.

According to the research team, while such games briefly captured audiences, they failed to adapt to growing player expectations and technological constraints. They were left to archives or collectors’ cabinets. Only those that transcended their design space survived.

Among the enduring arcade machines is the Strength Tester, measuring the force of a punch. Prof. Spiridonov compares such games to biological living fossils: “Like coelacanths or horseshoe crabs, they survived almost unchanged because they found stable niches where their function remains relevant.”

Innovation versus imitation

“The analysis of arcade games revealed that innovative genres, aligned with technological progress, were able to persist longer. Fighting games such as Mortal Kombat or racing simulations like Daytona USA relied on increasing CPU speed and ROM size. Meanwhile, maze or simple shooter games, trapped in a restricted design space, became oversaturated with imitations and collapsed,” Prof. Spiridonov argues.

According to researchers, the logic of cultural macroevolution is especially clear here: genres that failed to expand into new technological niches did not survive, while those that exploited the available resources maintained long-term viability.

“The development of a game is determined by its internal logic, which sets the possibilities and constraints for further evolution. It is similar to unicellular and multicellular organisms. Multicellular ones can be very small or very large. Unicellular ones are far more limited in size – they are like a single ‘building block,’ while multicellular organisms consist of many ‘blocks’ that can be combined in countless ways,” Prof. Spiridonov illustrates.

Technological niches and broader lessons

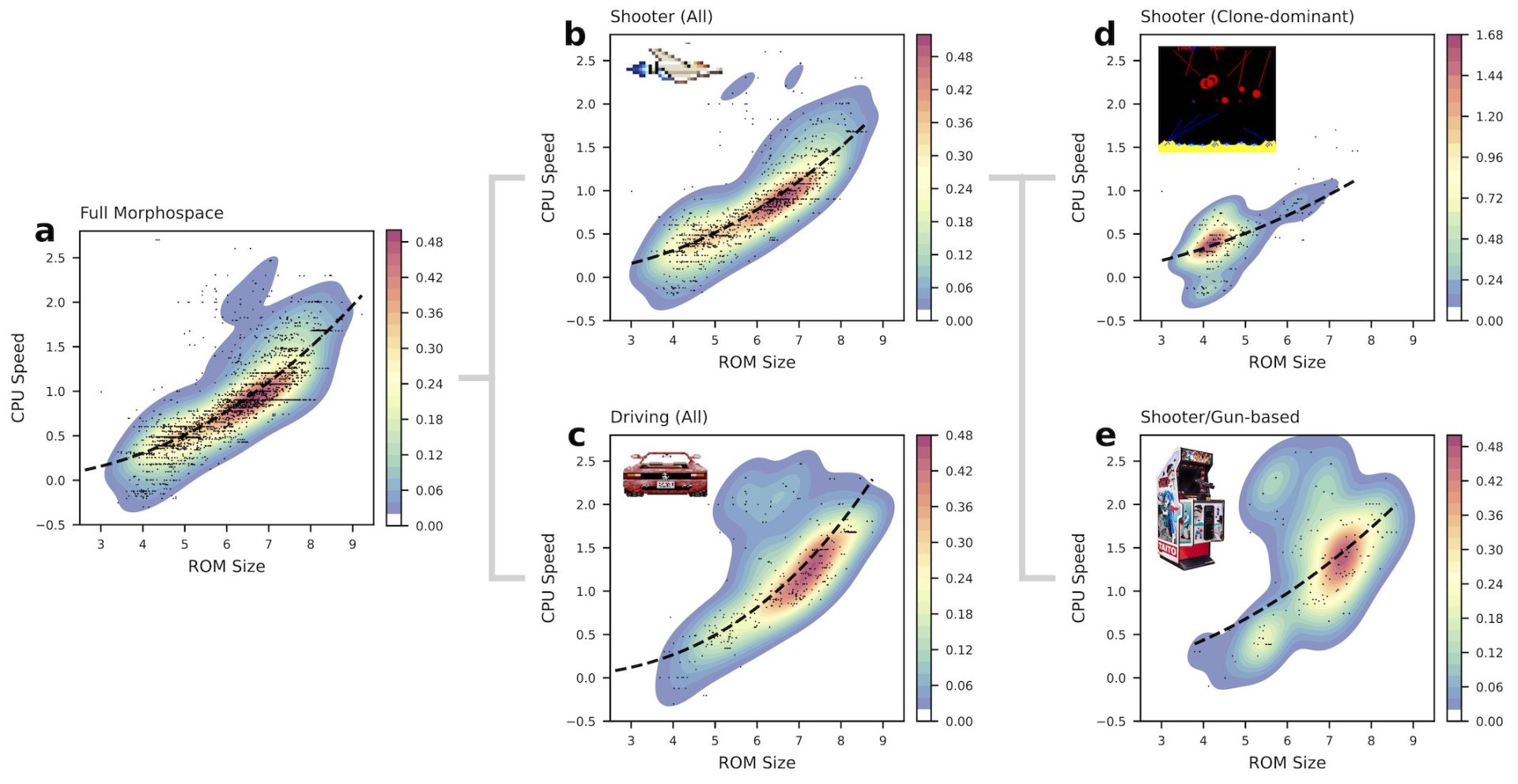

One of the most striking outcomes of the study is the morphospace map – a two-dimensional representation where games are positioned according to their technological traits (CPU speed and ROM size). This visualisation showed how technological constraints shaped genre trajectories. Games that exploited increasing computational resources could expand, offer more complex gameplay, and remain attractive longer. By contrast, genres trapped in restricted niches became saturated with imitation and quickly lost attention.

The concept of morphospace was first introduced by palaeontologist David Raup, who created a simplified yet comprehensive model of shell forms – the so-called “museum of all shells.” Morphospaces reveal how biological or evolutionary phenomena distribute along essential variables. A similar approach can be applied to cultural domains, where systems occupy their own unique niches.

“Innovation is always closely linked to technological resources. When creators could exploit more powerful hardware, new niches opened. Those confined to limited design spaces eventually lost appeal. This is a lesson not only for the history of games but for any creative industry,” Prof. Spiridonov stresses.

The professor also highlights that arcade games provide a powerful model for studying cultural macroevolution. This story is more than nostalgia: the arcade world was a laboratory where we could observe general principles of cultural evolution. While technologies are different today, the challenges remain strikingly similar.

“This study reveals a common developmental logic: explosive growth, saturation, decline, and the persistence of ‘living fossils’ are stages characteristic of all evolving systems. This trajectory applies not only to technologies but also to cultural phenomena – from literary genres to religious beliefs – only the timescales differ. Today, we can see a similar process in the dynamics of social media: after long-term growth and the dominance of hegemonic giants, more users are seeking niche platforms or even consciously rejecting excessive internet use. This may be the beginning of decline and a transition to something new,” Prof. Spiridonov concludes.